Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death

December 7, 1897

Tom commited his first murder on Dec. 12, 1895, killing John N. 'Jap' Powers and was hired to do it. He later rode with butch Cassidy's 'Hole in the Wall' Posse. Will Christian was known as 'Black Jack' and when he was killed in 1879 someone mistakenly identified Tom as 'Black Jack' and people started calling him that. Tom Ketchum, an attested but unconvicted killer and the most notorious outlaw in the Southwest, was soon to become the first person to suffer public judicial execution for merely attempting to rob a railroad train. A bad life was about to end for a bad reason. PLEASE NOTE I HAVE REDONE THIS VIDEO AT: PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS CONTAINS PHOTOS OF A DECAPITATED. Tom Ketchum nickname(s): Black Jack, Black Jack Ketchum, Tom Ketchum, Thomas E. Tom Ketchum date of birth: October 31, 1863. How old was Tom Ketchum when. Nov 23, 2016 It was April 26, 1901, when train robber Thomas Edward Ketchum, later known as Black Jack, was hanged in the town of Clayton. Ever since that fateful day, the sad, twisted tale of one of the last outlaws of the Wild West has captured the imagination of historians and Wild West enthusiasts alike.

Two cowboys, Dave Atkins and Ed Cullen, step inside the Steins Pass train depot in southwestern New Mexico a few minutes past 6 p.m. and make small talk with Charles and Daisey St. John. Then the cowboys pull pistols and rob them.

Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Photo

Some time before 8 p.m., the outlaws take their prisoners to the railroad and express office where they are joined by Sam Ketchum, and in a few minutes, Tom Ketchum and Will Carver, who have just finished cutting the telegraph wire.

Tom and Will round up all the horses and ride two miles west of the station where they build a bonfire on either side of the tracks, right below Steins Mountain.

As westbound train number 20 chugs up the grade from Lordsburg, one of the robbers sends St. John out to turn on the red light, signaling the train to stop.

When the train halts and the conductor and brakeman run into the agent’s office for their orders, they are met by drawn six-shooters and a command: “Get your hands up and keep quiet.”

Three shots are fired, perhaps for effect, as the robbers run out and mount the engine and make their demands on engineer Tom North.

As the train pulls out of the station, leaving behind the conductor and brakemen, the passengers and the express car guards assume the shooting was a prank and relax. Several minutes later, though, the train approaches the bonfires and stops. Finally, it sinks in that the train is in the hands of robbers. The express agents douse the lights, arm themselves and throw open the doors. Luckily, they have the help of two extra shotgun-wielding guards, C.H. Jennings and Eugene Thacker, who were hired because of rumors of a possible robbery.

Engineer North is brought out of the locomotive and ordered to uncouple the express car so the robbers can take it up the tracks and blow the safe. While the engineer works on the coupling, one of the express guards yells out, “No parleying will be allowed,” and fires a shotgun blast for emphasis. The outlaws fire back and North, caught in the crossfire, accidentally sets the air brakes, immobilizing the train.

The outlaws call for the messenger’s appearance but the demand is met by another shotgun blast from the express car.

The bonfires have unintentionally made perfect targets out of the bandits, so four of them scramble up on the engine to get out of the line of fire. Ed creeps forward under the tender and peers around the corner at the express car opening, watching his fellow outlaw (believed to be either Will Carver or Sam Ketchum) try to crawl under the express car with dynamite. The dynamite never ignites because expressman Jennings sprays buckshot at the outlaw, hitting him in the lower body.

The fight blazes for a half hour with the firepower of the expressmen’s shotguns besting the five outlaws. Sam Ketchum catches two buckshot in his scalp.

Dave Atkins yells, “Sam, I’m shot.” Sam inquires, “Where?”

“In the leg,” Atkins responds.

A disgusted Sam Ketchum spits, “Well, you white-livered-dude, go on shooting. I’m shot twice in the head.” *

All five of the outlaws receive lead from the agents’ shotgun fuselage.

By 9:15, the expressmen load their shotguns with the last of the ammunition (said to be “blue whistlers”) and no doubt are fretting their options. Peering out into the bonfire-lit night, Jennings spots Ed Cullen reaching into his cartridge belt. Jennings pulls the trigger on his last load, hitting Cullen in the head.

“Boys, I’m dead,” moans Cullen, as he crumples to the tracks.

The dramatic and gory shooting takes the heart out of the robbers, and they hobble to their hobbled horses and disappear into the night.

* Attributed to 1901 newspaper reports of Tom Ketchum’s statements before his hanging.

Lit Up and Shot Down

The Black Jack Ketchum gang members probably thought they were doing themselves a big, strategic favor with the twin bonfires: better to see if anyone gets off the train or tries to sneak up on them. They did not count on the express guards throwing open the door and aggressively defending their positions. The tables were turned and the bad guys were exposed, lit up and all shot down by buckshot.

The gang riding at Steins included: Tom Ketchum, an orphan, raised by his brothers, who left his Texas home to become a trail driver, but after committing a murder, he fled. Soon after, he and his brother Sam Ketchum killed two men in New Mexico and hit the Owlhoot Trail for good—and bad. Train robberies and a flurry of lurid crimes followed. Also riding with the Ketchums was sometime Wild Bunch Gang member Will Carver, killer Dave Atkins (some believe he was the leader at Steins) and a relative novice with a goofy handle, Ed “Shoot’em Up Dick” Cullen (sometimes misspelled as Bullen or Bullin), a cowboy and ranch cook for the Erie Cattle Company in Cochise County, Arizona.

Cullen earned his nickname when he told a Chinese restaurant owner, who was ordering him to pay his bill, that he was “Shoot’em up Dick” and he wouldn’t take any more guff. Supposedly, the Chinese retrieved a six-shooter and pointed it at Cullen saying, “I ‘Shoot’em Up Sam.’ You pay.”

A Damning Trail

Arriving at the holdup scene within an hour and a half, the assembled lawmen clearly see the tracks of the fleeing outlaws, but they decide to wait until daylight to give chase. In the morning, the posse (nine from Arizona and five from New Mexico) follows the trail southwest, then splits into two groups: one group follows the established trail, while the other, led by Jeff Milton, trail southward in a parallel route, coming out through Skeleton Canyon. The groups meet up near Tex Canyon at the south end of the Chiricahua Mountains.

In addition to an abandoned bloody handkerchief with the initials “T.K.” found at Steins, the lawmen gather the following clues on the trail: an abandoned horse still saddled and a discarded pair of overalls with a bloody hole in the pants leg.

Some 75 miles from Steins, the tracks enter the mouth of Tex Canyon and lead straight toward a lonely bunkhouse. Around noon, the posse rushes the building and arrests three cowboys: Len Alverson, Walter Hovey and Bill Warderman. When two other cowboys, Tom Capehart and Henry Marshall, ride up, they are also arrested.

The circumstantial evidence is damning: Hovey is nursing a bullet hole in his leg that matches the hole in the discarded overalls and posse members find 1,000 rounds of ammunition in a wagon on the property, in addition to “enough blasting fuse and giant powder to blow up all the trains on the western continent.”

Interviewed separately, the suspects give conflicting stories. Hovey claims his leg wound was caused when he and others ambushed Mexican smugglers. Alverson claims they robbed a man of mescal near the border and in a drunken stupor he, Alverson, tripped and his gun went off, the “ball ranging up through the calf of Walter’s leg, coming out just below his boot top.” (When Tom Ketchum was captured in 1898, the examining doctor noted “a number of scars on left leg above the knee.” Were those discarded overalls his? Quien sabe?)

Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Row

Although the eager posse members try to pin the bloody handkerchief on Tom Capehart (desperately mangling his last name to Kapehart to make it fit the T.K. monogram), it is likely the initials stood for Tom Ketchum.

A mile and a half farther up Tex Canyon, at least three of the wounded outlaws who actually did try and rob the train at Steins are waiting and watching from a cave-riddled escarpment known as the Wildcat.

Close Enough For Government Work

The five cowboys arrested in Tex Canyon—Hovey, Alverson, Warderman, Capehart and Marshall—are taken to San Simon, Arizona, then Tucson. On the first leg of their journey, the posse members and their prisoners pass right by a high canyon hideout called the Wildcat, where the real train robbers watch from their lofty perch.

By Christmas, the Tex Canyon five are in jail in Silver City, New Mexico. By February, all five, plus the owner of the ranch, Mr. Vinnedge (alias Cash), go on trial. The jury evidently decides keeping bad company isn’t a crime and, out only 15 minutes, returns with a not guilty verdict.

Officials led by U.S. Marshal Creighton Foraker successfully retry the men on separate federal charges (feloniously tampering with U.S. mail during the attack on the post office at Steins). This time, a jury in Las Cruces finds Capehart, Marshall and Vinnedge not guilty (although all three spend another five weeks in jail over bond issues). Warderman, Hovey and Alverson are found guilty and are kept in Pat Garrett’s jail. The hard luck trio of cowboys finds itself at the Santa Fe Penitentiary in September 1898, facing ten years in prison, plus a $500 fine and liable for $7,000 in court costs.

A year later, as Sam Ketchum lay dying in the Santa Fe Penitentiary, he clears the three of any involvement in the Steins Pass holdup. A year after that, in 1901, an hour before Tom Ketchum walks to the gallows, he confesses his involvement at Steins and also clears the three men of participation.

Yet not until a presidential pardon from Teddy Roosevelt, more than five years after they entered prison, do the men get released.

Many in the territories still believe they are guilty. If guilty of anything, Hovey, and probably the others, did know the Ketchum crew was hiding at the Wildcat, both before and after the robbery. Hovey later says, “I never gave a posse a clue to their whereabouts, and I gained the enmity of officers by my refusal.”

Boy, Howdy! Did he ever.

Winners and Losers

The U.S. marshal for New Mexico Territory, Creighton Mays Foraker, actively persecuted the case. Express Guard Eugene Thacker, the son of Wells Fargo Detective John Thacker, was one of the heroes of the Steins Pass gunfight. He was only 19 at the time of the robbery.

The three Tex Canyon cowboys who served five-plus years in the Santa Fe Penitentiary are sketched at left, from top:?Bill Warderman, Leonard Alverson and Walter Hovey.

Jeff Milton led one of the posses that rounded up the cowboys in Tex Canyon. He was joined by George Scarborough, who worked as a range detective out of Deming. Scarborough’s undercover work ultimately did in the robbers.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

After the narrow escape from Tex Canyon, the Ketchums and Carver fled back to Texas, where they held up two more trains. After another train robbery, a posse from Cimarron, New Mexico, badly wounded Sam Ketchum during a blazing gunfight in Turkey Creek Canyon. Sam escaped but was captured at a ranch and taken to Santa Fe. Sam died from his wounds in the Santa Fe prison on July 24, 1899.

Tom Ketchum was kicked out of his own gang, then captured after trying to single-handedly hold up the Folsom Flyer near Robber’s Cut (so-called because members of the gang stopped trains there on three different occasions). Tom lost his arm in that affair and, subsequently his head, when he was hanged for his crimes in Clayton in 1901.

Will Carver made it to Fort Worth, Texas, in time to appear in the legendary Fort Worth Five photo, but he ended his career in a hail of bullets in Sonora on April 2, 1901.

Of all the known robbers in on the Steins Pass affair, Dave Atkins certainly ranged the farthest. After turning himself in to police in Butte, Montana, he was extradited back to San Angelo, Texas, where he found out his wife had divorced him and remarried. Jumping bail, he joined the Kaffrarian Rifles (a cavalry group) and fought in the Boer War in South Africa in 1900. After a trip home to Texas in 1902, he soon departed for Belize and Honduras, traveling widely in Mexico and South America. He returned home in 1919 and, after serving a prison term, he was judged insane in 1932 and placed in the State Hospital at Wichita Falls, where he remained until his death in 1964. He was 90.

Recommended:Lawmen, Outlaws And S.O.Bs.: Volume II by Bob Alexander, published by High-Lonesome Books; and The Deadliest Outlaws by Jeffrey Burton, published by Palomino Books.

Photo Gallery

Related Posts

Terry Kelley Ruidoso Downs, New Mexico The favorite sanctuaries for Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch were…

An African slave, Esteban de Dorantes, or Estevanico, helped spread the idea of Seven Cities…

In the past 60 years, True West has consistently provoked one’s urge to hit the…

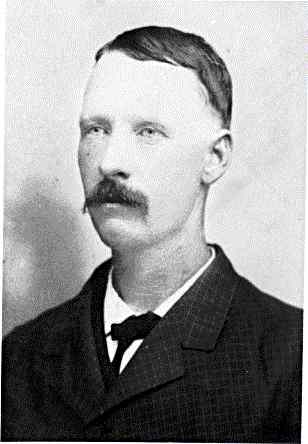

Texas cowhands-turned-outlaws Tom and Sam Ketchum, along with range pals like David Atkins and Will Carver, robbed trains and became notorious in the Southwest.

By Jeffrey Burton

At almost 1:15 on the afternoon of Friday, April 26, 1901, a one-armed man in a black suit hurried up the 13 steps of the gallows at Clayton, Union County, New Mexico Territory. Tom Ketchum, an attested but unconvicted killer and the most notorious outlaw in the Southwest, was soon to become the first person to suffer public judicial execution for merely attempting to rob a railroad train. A bad life was about to end for a bad reason. And the ending would be worse, for he would not die in the officially approved fashion-from breakage of the neck vertebrae-but from decapitation at the rope's end.

At 17 minutes past the hour, and at the second attempt, Sheriff Salome Garcia's hatchet sliced through the control rope, the trap was sprung, and in a moment or two Tom Ketchum had made history-twice. The clicking cameras mounted beside the stockade snapped again and the ghastly scene was captured for all time: There, held on its side by a doctor and a deputy sheriff, was the body of Thomas Ketchum, and there, in the bloodied black hood held in place by horse-blanket pins, was Ketchum's severed head.

'Nothing out of the ordinary happened,' Sheriff Garcia declared. 'No bungling whatever. Everything worked nicely and in perfect order.' Like many of the others present, the sheriff probably was not lastingly discomforted by the horrifying spectacle of butchery that had been enacted before his eyes. It was a bad and hard way to die, but Ketchum, manifestly, had been a bad and hard man.